If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by terms like “relative minor,” “parallel minor,” “natural minor,” “harmonic minor,” and “melodic minor,” you’re not alone! Understanding the differences between these terms is essential for mastering music theory, but it doesn’t have to be confusing. Let’s break it down into simple, easy-to-follow explanations.

Understanding Relative vs. Parallel Minor

Think of minor scales as belonging to two main categories:

Parallel Minor – Shares the same starting note (root) as a major scale but has a different key signature.There are a lot of descriptive terms that are associated with minor scales. For example, you’ve probably hear the terms “relative” minor, “parallel” minor, “natural” minor, “harmonic” minor, and “melodic” minor. What does it all mean? What are the differences between each? Do I really have to memorize all of them?

Relative Minor – Shares the same key signature as a major scale.

Students generally get confused because they lump all of these varieties of “minor” into the same basket. It is much easier to think of these descriptive terms in two separate categories.

Relative and parallel minor refer to a tonal center; natural, harmonic, and melodic minor refer to various modes of a minor scale. In this article, we’ll make sense of the terms “relative” and “parallel” minor.

Relative minor is related to a major key. the major and relative minor key share the same key signature. Let’s take a look at how this works.

Below are two scales, F major and D minor.

Notice that both scales have the same key signature (one flat, Bb). Notice that the individual notes in both scales are exactly the same, the only difference being the starting note of each scale. Because these two scales share the same key signature, and therefore the same individual notes, we call them relative.

The next logical question regarding these related major and minor scales might be, “How do I know which minor scale is related to a given major scale?” The answer is that the relative minor scale is based on the 6th degree of the major scale. Sound confusing? Let’s explain.

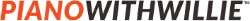

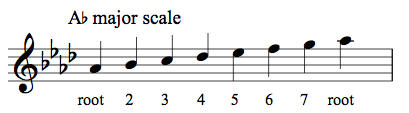

First, we’ll take a major scale, any major scale. In this instance we’ll use the key of Ab major, which has 4 flats – Bb, Eb, Ab, Db. Notice that we’ve labeled each degree of the scale.

The relative minor can be formed by finding the 6th degree of any major scale. In this example, the 6th degree of Ab major is F. So if we play the same scale (with the same key signature) starting on F, we will have played an F minor scale (natural minor).

What is a Parallel Minor Scale?

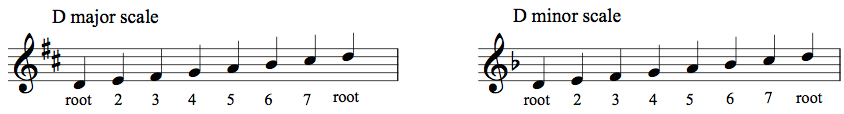

Unlike relative minors, parallel minor scales do not share the same key signature as their major counterparts. The only thing they have in common is their starting note (root).

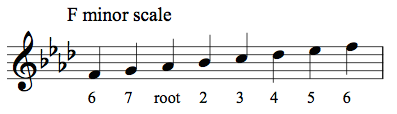

Let’s take the key of D major. The relative minor of D major is B minor, because ‘B’ is the 6th degree of the D major scale and B minor shares the same key signature as D major. The parallel minor of D major is D minor. The only thing that is shared is the root, or starting pitch.

In order to convert a major scale to a minor scale (natural minor), the 3rd, 6th, and 7th degrees are lowered by a half-step.

Quick Recap

- Relative minor scales share the same key signature as a major scale (found on the 6th degree of the major scale).

- Parallel minor scales share the same root note but have a different key signature (created by lowering the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes of the major scale).

What’s Next?

Now that you understand relative and parallel minors, the next step is exploring the different modes of minor scales: natural, harmonic, and melodic minor. Stay tuned for a breakdown of these exciting variations!

By understanding these concepts, you’ll improve your ability to read music, compose, and improvise with confidence.

Happy playing!